|

Alan Godsal was born on 4th May 1894 in Hawera, New Zealand to Edward and Marion Godsal.

He was the third oldest of five children and his father was a farmer and land owner in the South Taranaki region.

In about 1900 the family returned to England, and lived at first in Ranby, Milnthorpe Road, Eastbourne.

Alan suffered ill health and spent some time in Borough Sanatorium, Longland Road, Eastbourne.

In 1905 he followed in the footsteps of his older brother Hugh and became a boarder at Oundle School, Northamptonshire, firstly as a member of Berrystead and subsequently within School House.

Alan had overcome his earlier illness and was a keen participant in a range of sports including bowls, rugby and rowing.

Alan's Headmaster at Oundle was Frederick Sanderson who played a leading role in establishing Oundle as a major public school.

He believed in teaching students what they wanted to learn, and as a result introduced subjects such as science, modern languages, and engineering to the curriculum.

By Alan's time, Oundle had become the foremost school for science and engineering in the country.

Though not a noted academic, Alan was a prize winner at drawing and competed in shooting competitions as a Lance Corporal in the Cadet Corps.

He worked hard at his rowing and was in the school squad for the fours in 1912.

Alan left Oundle a year later and by the start of the First World War was living with his family in Winnersh Lodge.

On Tuesday 18th August 1914 Alan applied for a temporary commission in the army at Reading Barracks and, in keeping with family tradition, requested a posting with the Royal Engineers.

Alan was interviewed by the Depot Commander and also passed a medical.

His old headmaster acted as a character witness and because Alan was under 21 years of age his father had to countersign the application.

Within a few days Alan found out that more experience and special training were required for the Engineers and so he wrote from Haines Hill changing his preference to an infantry regiment based at Aldershot.

He was first assigned to the 6th Battalion of the Royal Berkshire Regiment and then on 22nd September 1914 Alan was gazetted as a Second Lieutenant in the Rifle Brigade.

He was Battalion Machine Gun Officer in 7th Battalion at the time of his death.

On 20th May 1915 Alan's Battalion sailed for France on S.S. Queen, departing from Folkestone and disembarking at Boulogne where they marched to a rest camp.

Over the next week the Battalion moved eastwards, firstly to billets at Watten and then on to Zuytpeene, Fletre and finally over the Belgian border to Dranoutre.

Here the Battalion joined with 46th Division for two weeks of training.

They were attached, two companies at a time, to the 5th Lincolnshire Regiment and 4th Leicestershire Regiment for instruction in trench warfare.

Fresh from training 7th Rifle Brigade moved into the front line and suffered their first casualties from enemy action on 12th June — three men killed and three wounded.

After just a few days in the trenches the Battalion was on the move again, first to Poperinge and then to huts at Vlamertinge near Ypres.

The Battalion was in reserve and spent time on fatigues — cleaning the huts and digging communications trenches east of Ypres.

Though not on the front line, the working parties and the camp came under periodic shellfire and further casualties were sustained.

On 30th June, 7th Rifle Brigade started their first eight day stint in the front line at Hooge on the Ypres salient.

Hooge lies a short distance east of Ypres and at the time was the scene of heavy fighting.

This sector was described in the Official History as having an 'evil reputation'.

The British held the Chateau and Stables but were under constant threat from German positions nearby.

7th Rifle Brigade were back in reserve on 19th July when, to relieve this threat, the British exploded a mine under a German strongpoint creating a crater of 120 feet in diameter.

This allowed troops to advance into the German front line trenches on its far side.

Once the situation had stabilised the Battalion commenced its next spell at the front in the trenches around the rim of the crater.

Now the opposing trenches were very close and there was little defensive wire.

The situation was volatile and the Germans started to attack the position by exploding a mine and digging a trench to within 15 yards of the crater.

Bombing duels and trench mortar attacks became regular occurrences.

On 25th July there was a dogfight overhead that resulted in a German plane crashing in flames in nearby Zouave Wood.

Late on 29th July the 7th Rifle Brigade began to hand over the trenches to its sister Battalion, 8th Rifle Brigade.

It was a dark night with the moon in the 3rd quarter and the relief was difficult because the trenches were deep and narrow making movement along them extremely awkward.

Every day minenwerfer bombs blew in parts of the support trenches rendering them unusable, so more men had to be crammed into the front line.

The isolated nature of the position also made communication with Brigade H.Q. difficult.

These factors meant that the usual practice of sending in one company, together with machine guns and bombers, some hours in advance of the main body had not been followed.

The relief was finally completed by 2 a.m. on 30th July 1915 and 7th Rifle Brigade lent their machine guns to 8th Rifle Brigade overnight as part of the change-over.

The new troops had barely settled into this precarious position when the German attack started.

In addition to the element of surprise upon newly introduced troops, the Germans brought a new and frightening weapon into the fray.

At 3.15 a.m. with dramatic suddenness, the ruins of the Stables were blown up, and jets of flame shot across from the German trenches.

This was the first time that the British had faced liquid fire flamethrowers and they were totally unprepared.

At the same time a deluge of trench mortars and bombs fell on the 8th Rifle Brigade, with shrapnel raining on all of the support positions back to Zouave Wood and Sanctuary Wood.

The ramparts of Ypres and the exits from the town were also shelled.

The attackers achieved complete surprise and the immediate effect was to drive back and disorientate the defenders, allowing the German infantry to move forward.

Meanwhile 7th Rifle Brigade had reached its rest billets at Vlamertinge, west of Ypres, at 3:45 a.m. after a march of over eight miles in the dark.

At 4:45 a.m. they were put on the alert, and at 5.30 a.m. orders were received to return to Ypres — tired and unwashed - with as much small arms ammunition as possible.

Water bottles were filled and rations and ammunition issued in time for the Battalion to start back at 7 a.m. Once in Ypres they halted on the road between the Asylum and Kuisstraat until 11.30 a.m. while the Commanding Officer and Adjutant went to the 41st Brigade H.Q. at the Ramparts to receive orders.

The orders were to march via Zillebeke to Zouave Wood and join up in support of the 8th Rifle Brigade in counter attack.

Slow progress was made as the communication trench was very muddy and the head of the Battalion reached Zouave Wood about 1.40 p.m.

At 2 p.m. a bombardment by the British artillery began, lasting three quarters of an hour, during which the Battalion formed up in the wood at the rear of what remained of the 8th Rifle Brigade.

From there 7th Rifle Brigade were thrown into the counter attack to try to regain some of the day's losses.

The Battalion’s machine guns had been lost during the night's action and the C.O. decided to keep the machine gunners close to his HQ in Zouave Wood in case any of the guns could be recaptured.

The following excerpt from Ruvigny's Roll of Honour describes the circumstances of Alan Godsal’s death:

|

It is clear from the statement of Corpl. Molloy [believed to be 5431 Michael P Molloy],

who was within 20 yards of Lieut. Godsal when he was killed,

that Lieut. Godsal did himself advance from this position and get possession of at least one of the guns,

for the Corpl. saw him firing it at the enemy,

and later saw him firing his revolver — probably when he recovered the gun he picked up only a small amount of ammunition — and later still heard a shout that he was killed,

a shell having struck him in the face.

Private King [believed to be B/2829 Frank King] gallantly endeavoured to pull his body back into the trench and was himself killed instantaneously.

Corpl. Molloy accounts for Lieut. Godsal's recovering the gun by saying that he knew every yard of trench and ground as he was out frequently day and night making daring reconnaissances.

The Corpl. added that if ever anyone deserved the V.C. he did.

|

Despite the heroic efforts of 7th Rifle Brigade the counter attack failed and the positions around the crater and Chateau were lost, despite intensive fighting.

On 2nd August 1915 Alan Godsal's parents received the terrible news of their son's death by telegram:

|

Deeply regret to inform you that 2nd Lieutenant Alan Godsal 7th Rifle Brigade was killed 31 July.

Lord Kitchener extends his sympathy.

Secretary War Office.

|

A few days later a statement by Private Bray of the Shropshire Light Infantry confirmed the circumstances of Alan's death:

|

In front of Hooge Chateau in Sanctuary Wood there were about 200 dead of various regiments.

We covered the lot up.

I noticed this body because the lower limbs were charred with liquid fire.

We reported it but possibly the officer to whom I reported it may have been wounded or killed.

|

Further details are provided by the Oundle School memorial book reads:

|

...his Colonel described him as 'quite my most promising Officer'...

Godsal recaptured one of his machine guns and used it against the enemy until ammunition failed, and he was last seen using his revolver.

His body lies in what was the Sanctuary Wood.

One of his men said: 'I shall never have such an officer again.

All of us loved him.'

|

Alan was twenty-one years old and had been on the Western Front for only ten weeks.

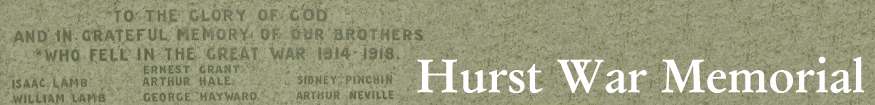

He has no known grave and is commemorated on the

Menin Gate Memorial along with nearly 55,000 other missing soldiers.

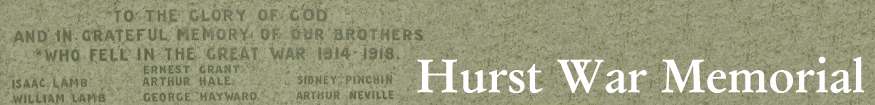

Alan is remembered locally on a brass plaque in St. Nicholas Church, Hurst which reads:

In honour of our Lord Jesus Christ

and in memory of

Alan Godsal

2nd Lieut: and Batt: Machine Gun Officer

7th Bn Rifle Brigade: younger son of

Edward Hugh & Marion Grace Godsal

and nephew of William Charles Godsal

of Haines Hill. Born at Hawera New Zealand

May 4th 1894. Killed in Action at Hooge

Flanders July 30th 1915.

Be thou faithful unto death and I

will give thee a Crown of Life.

|

Alan is also commemorated on a memorial in the Chapel of St. Anthony at Oundle School.

His older brother

Hugh

also fought in the First World War as an officer in the Royal Field Artillery.

He was seriously wounded and mentioned in despatches.

|